Written by Richard Jacklin

Commercial Lead – Space & Satellite

Space environments present unique sensing challenges. Systems must detect objects ranging from paint flecks to spacecraft components, operate reliably in harsh conditions, and do so with minimal mass and power consumption. mmWave radar addresses these requirements, providing millimetre-scale resolution with practical implementation that suits the realities of space missions. But how does wavelength affect what a sensor can detect?

Identifying the best wavelength for space sensing

The wavelength of an electromagnetic signal plays a crucial role in determining the size of the objects you can detect. If the object is larger than the wavelength, the signal will tend to reflect strongly, making detection easier. However, if the object is smaller than the wavelength, the signal tends to bend or diffract around it, making detection more difficult.

Long wavelengths travel great distances and pass through many obstacles, which makes them ideal for long-range sensing. However, they lack precision. Think of a large ocean wave. If it encounters a small boat, the wave will mostly roll past it, barely disturbed. You might detect the boat from the way the wave changes, but you wouldn’t know much about its shape or details. These long wavelengths are excellent for detecting large objects but aren’t suited for detecting small objects nor picking out fine detail.

On the other hand, short wavelengths such as those used by lasers (of order a thousandth of a mm) are great at providing detailed information, but over a smaller area. Imagine shining a laser beam on a textured surface. Every bump and flaw will be highlighted, revealing intricate details about the surface. However, this kind of precision comes with trade-offs – it requires more time and energy to cover a large area, and it would only work in a very clean environment, since even dust particles would scatter the beam.

In practice, you need to choose a wavelength that is tuned to the size of what you’re looking for. If you go too small, you’ll end up obtaining more detail than necessary and risk interference from objects you don’t care about. This is especially important for missions on planetary surfaces, where the environment can be full of dust, though less of a concern in space, which is largely empty.

For FMCW radars the frequency difference between the transmitted and the reflected wave encodes the distance to that object

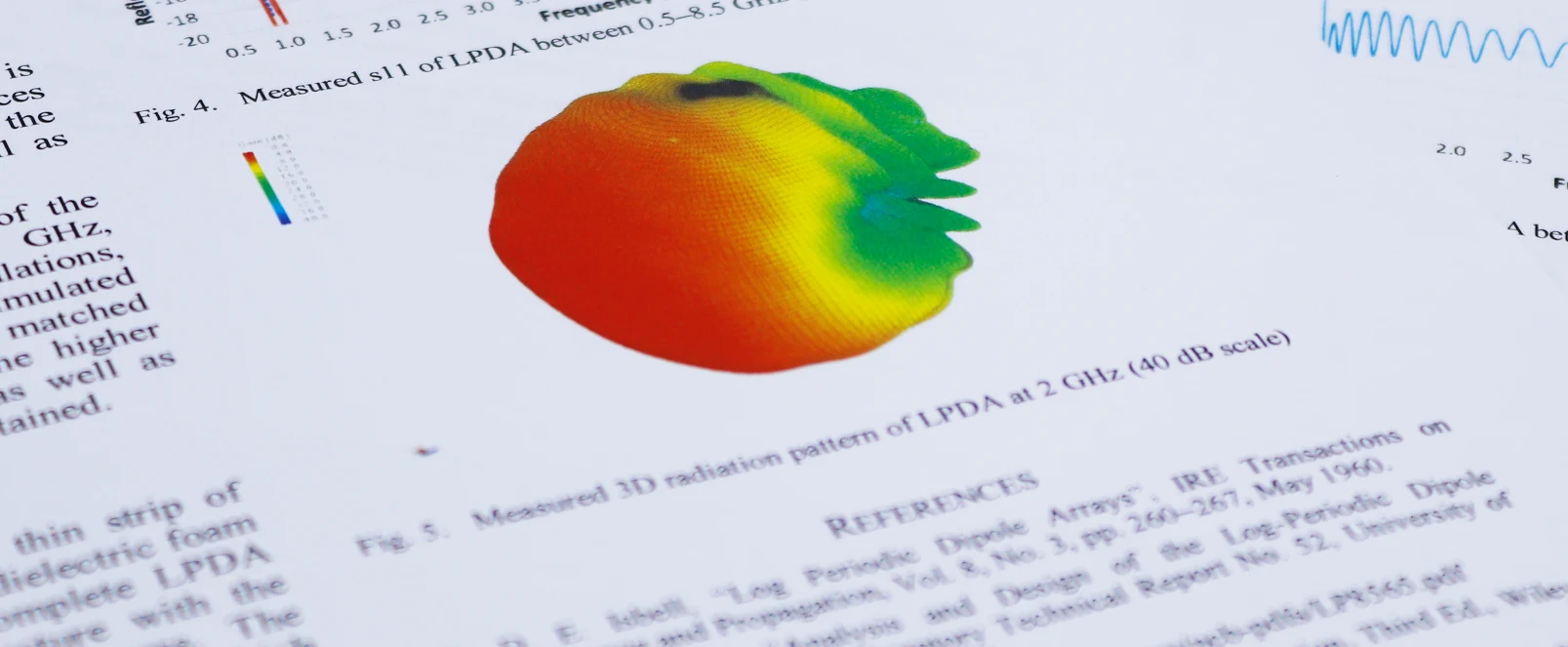

Wavelength alone doesn’t tell the full story, however. Radar systems typically transmit pulses that cover a range of wavelengths, i.e. they have bandwidth. Using just one wavelength can make it hard to tell the difference between two closely spaced objects. Frequency Modulated Continuous Wave (FMCW) radar, for instance, sweeps through a range of frequencies in each pulse and this in turn enables a radar to discriminate between objects at different ranges.

The ability to discriminate between objects at different ranges is called range resolution, and the range resolution improves with increased bandwidth. In FMCW radar, the duration of the pulse can be increased to improve the signal to noise ratio, to improve the radar’s ability to detect and distinguish between targets.

Why mmWave Radar?

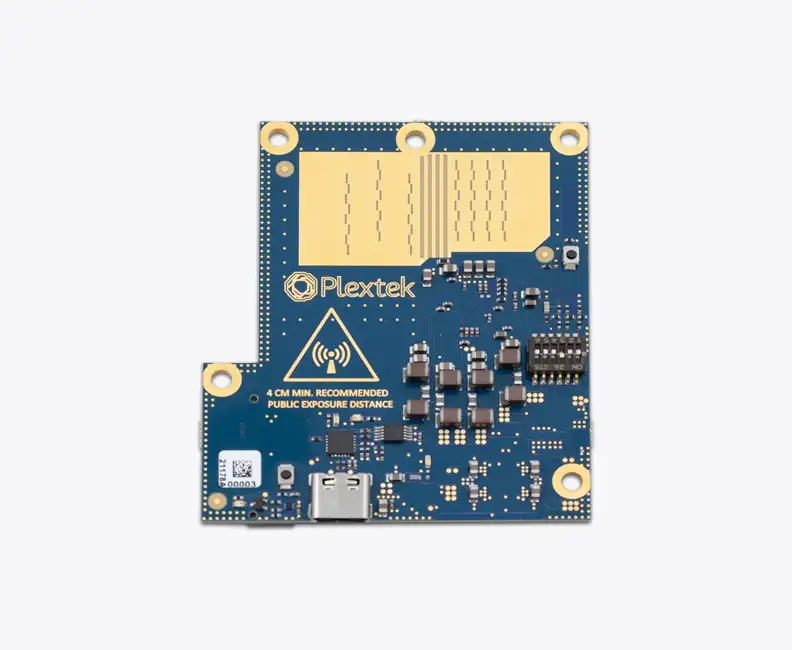

Radar has been around for a long time, but has recently advanced significantly in its detection ability, particularly thanks to research and innovations coming out of the automotive sector. This has led to mmWave radar. These operate at frequencies of 30–300 GHz, which as the name suggests, produces a wavelength of 1–10 mm.

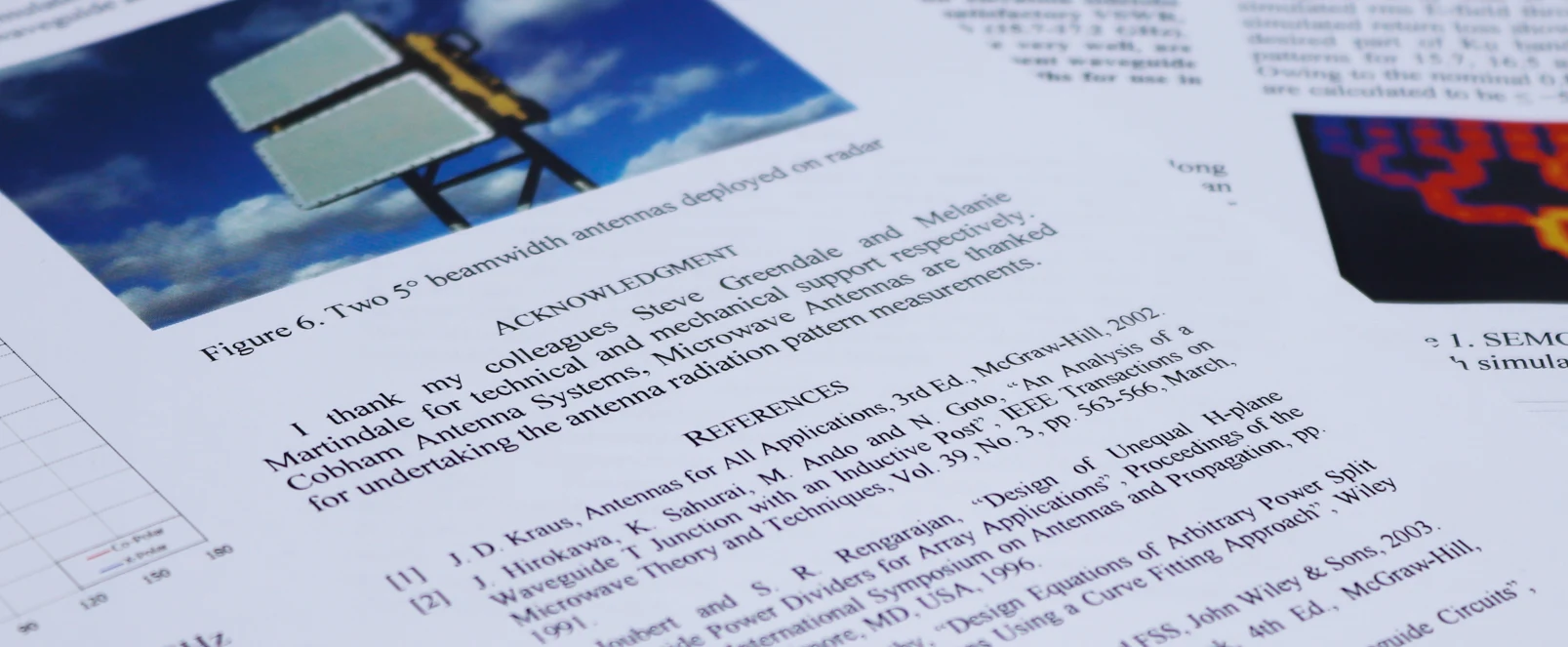

We argue that mmWave is the ideal balance for many space applications. It is much more accurate than traditional microwave wavelength radar (a few centimeters in wavelength), which has insufficient resolution for picking out smaller spacecraft features. mmWave radar is also cheaper and more practical than LiDAR, and although LiDAR has better resolution, such precision comes at a cost of high-power requirements and is rarely needed for most space applications.

- mmWave radar sits perfectly in the middle. It can have a wide field of view – an antenna can emit a wave that travels over a wide angle and detect objects down to a few mm in scale. That offers sufficient resolution to see small details like detached paint flecks or loose parts, and for navigation when docking to another spacecraft. It does all this with low weight and power requirements, and no moving parts.

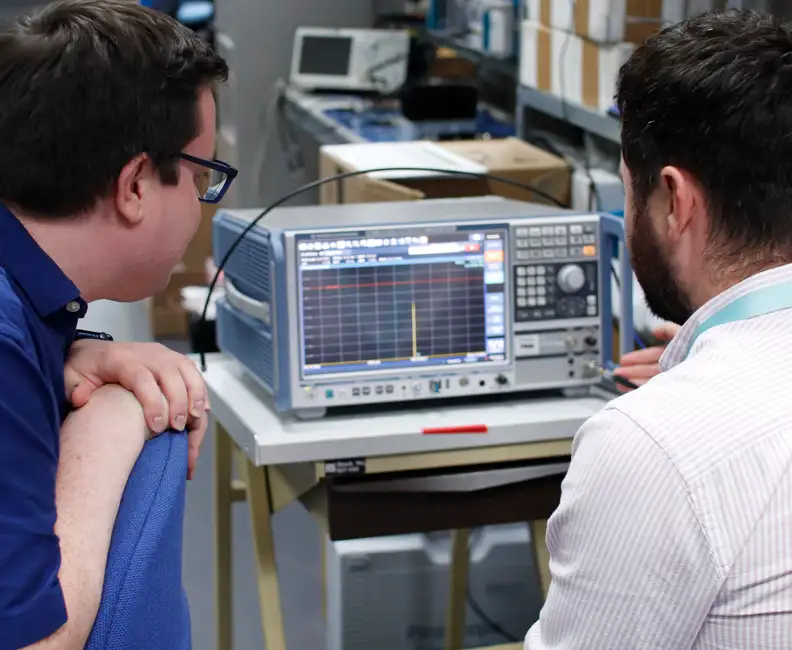

- Radar can measure the speed of objects, and movements within objects such as a loose part hanging off a satellite that is moving counter to the satellite trajectory, even at Low Earth Orbit speeds of over 7 km per second. This is achieved by measuring the Doppler effect, where the wavelength of the signal effectively gets squashed or elongated as it bounces off an object that is moving towards or away from it.

The phase difference between pulses encodes the target’s velocity

- Because space is fairly empty, radar is not impacted by unwanted clutter that would scatter mm-scale waves – it can just peer out and detect anything in its range. However, on lunar and planetary missions where sub-mm sized dust particles can obscure the view of a short wavelength LiDAR system, radar can continue to operate reliably due to its longer wavelength.

- A final benefit is that radar is not affected by the Sun. The main alternative, LiDAR, uses wavelengths in the infrared (IR) part of the EM spectrum. That means it can be interfered with by other IR sources, and the Sun is a big source. It is not dissimilar to how human eyes process information – they can detect phenomenal detail in good light but imagine trying to keep a plane in focus as it crosses between you and the Sun (don’t actually do this!). Although the Sun does emit waves in the radio frequencies used by radar, they are at far lower levels, have very low impact, and even where they are an issue, can be mitigated through signal processing.

Ready to explore how mmWave fits your space application?

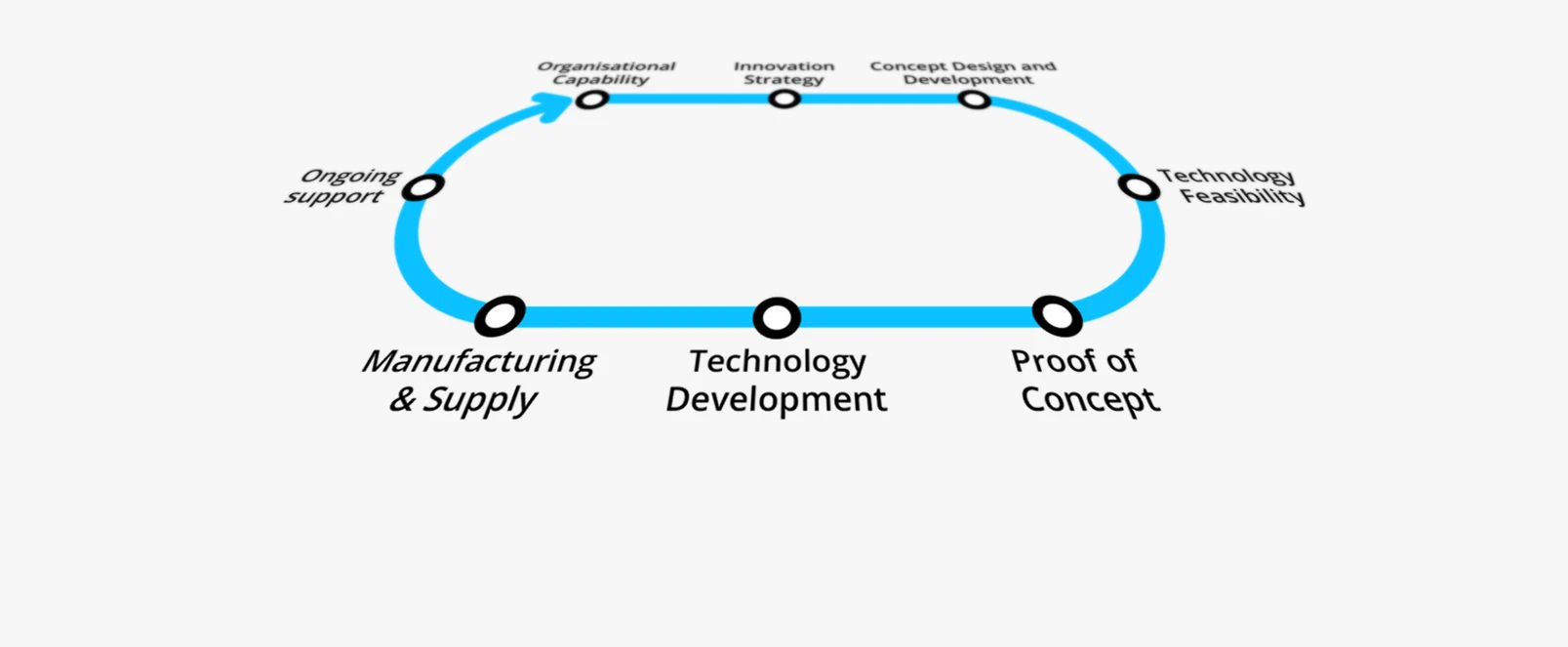

Our team brings proven expertise in mmWave technology for space applications, delivering precision performance whilst meeting the critical constraints that matter most: compact size, low mass, minimal power consumption, and cost-effective integration.

Let’s talk!